Business of Publishing, Part One

How I learned the business of art through film distribution. The first of a three-part subseries.

I plan to complete my novel, The Blue Jay, before the end of summer. And when I’m not writing and editing, I’m also researching the publishing industry. Until a few years ago, the business methods used by publishers would’ve been oblique and confusing to me. I used to wonder how they chose which books to publish, how they decided on the sizes of advances, whether they knew upon acquisition how well a book would sell. And I had a lot of romantic ideas about working with editors, approving cover art, and going on tours to book stores for reading and signing events. It all seemed glamorous yet mysterious.

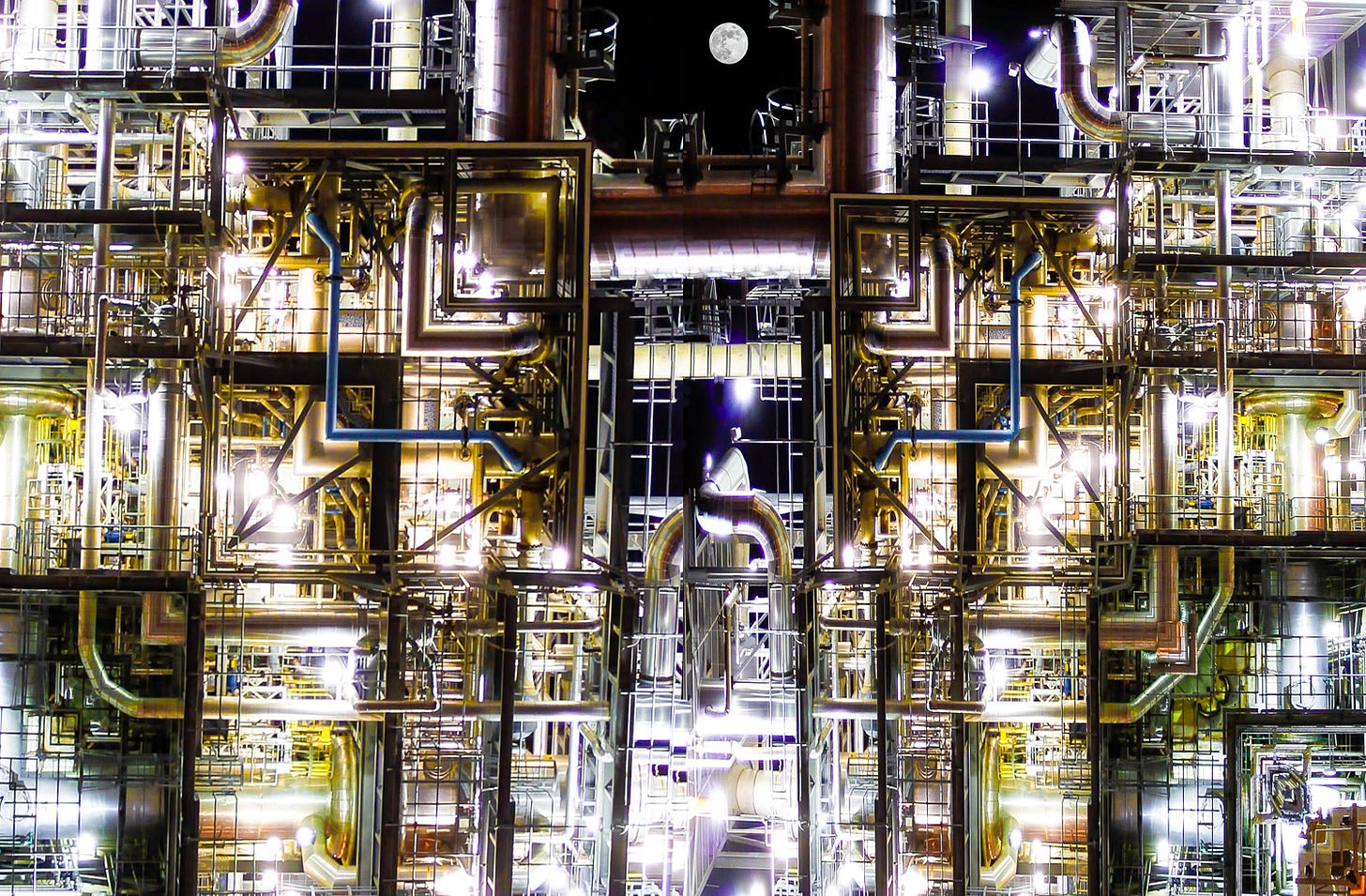

Today, I understand better than most beginning novelists how publishing works, because I’ve spent a dozen years in a similar industry: film distribution. All forms of art can be commoditized by the people who sell them. Publishers (interchangeable witih ‘distributors,’ ‘gallerists,’ ‘producers,’ etc.) view artwork as product, exactly the way a fertilizer formula, a plumbing part, or a pizza recipe are regarded in their respective industries. If that sounds cynical, it’s not intended to be. And while some might think selling art would take all the joy out of it, it doesn’t. When you have something good, you still get excited about it, and not just because of the profits you hope it’ll generate.

I’ve been fortunate to be employed at two prestigious distribution companies: New Day Films, and Kino Lorber, and to freelance for several others.

New Day is a co-op, founded in 1971 by four feminist filmmakers frustrated by mainstream distribution channels. By the time I joined in 2008, with my feature documentary Kansas vs. Darwin, the group had expanded to over 100 members, including at least two Oscar-winners. The membership selects films on the basis of quality, sales potential, and how they address a social issue. Since it’s a co-op, it’s just as important that the filmmaker appears to be a potential asset, with desirable knowledge and connections, and a willingness to do the hard work of self-distribution and keeping the organization running.

While there, I helped establish New Day’s nascent streaming platform, served on the steering committee, and lobbied for the membership to become more personally engaged with their buyers, through conferences and market events. In return, I gained knowledge about selling to institutions. But even though I frequently did well in sales, I profited relatively little, due to marketing expenses. I still had a lot to learn.

The camaraderie between members at New Day was awesome, but at that time, there wasn’t enough sharing about marketing tactics, and we lacked solid knowledge about the changing needs of our buyers. Most business decisions were made collectively at the annual meeting, which slowed all our processes considerably.

In late 2013, I managed to snag a job managing institutional sales at Kino Lorber, one of the most-respected purveyors of art-house, documentary, foreign and classic films. Kino was a nimble company, quick to spot opportunities, and smart about acquisitions. From their small, fifth-floor office on west 39th street in Manhattan, with a staff of about 30, we covered the gamut of distribution. It was a much more intense level of industry competition than I experienced at New Day, and decision-making happened rapidly all day, every day.

Under the direction of CEO Richard Lorber, our general strategy was to overcome the effect of slender profit margins by acquiring the rights to a large number of films all during the year, expecting a few to perform well enough to cover the shortfalls of the (inevitably) many that did less well. The workload it takes to release 50+ films per year was already overwhelming: Marketing and sales functions included copywriting, list purchases, email blasts, key graphics, packaging, shipping, two websites, streaming deals with several platforms (such as Netflix and Kanopy), soliciting reviews from outlets such as the New York Times, producing special DVD features, list-mining, and booking films and filmmakers for live screening events.

Gradually, I learned that my colleagues had a pretty good, if somewhat inconsistent, grip on how to size up what films would work better for each of their own departments (theatrical, streaming, institutional, community, and physical media). And so, the specific rights acquired for any film were generally in line with what we felt would benefit the company most. There were many compromises in acquisition and surprises in results, of course, but employees were granted the autonomy to adapt to new circumstances. And, the number of films being offered to us was huge, so if a title didn’t sell as projected, something else would always come along.

Among the less-experienced filmmakers who brought us the products of their incredibly hard work, I frequently saw an earlier version of myself, because many knew so little about the thin profitability and the labor involved at our end. Many times, they harbored unrealistic expectations of how their film would perform, and were disappointed when the numbers would rarely if ever reach hoped-for levels.

Learning distribution, with its endless intricacies, felt like the equivalent to earning a master’s degree in the commerce of art, and we never lacked for unpaid interns every season of the year. Smart artists want to learn this stuff. I’m still dismayed that it’s not taught as part of education in every art form, because an artist on their own generally won’t fare as well without this knowledge, and the most successful artists understand it very completely. Unfortunately, those who teach art usually have more experience with technique, technology, history and pedagogy, and little with commerce. And speaking as a filmmaker, there were many, many things about distribution I wish I’d understood better before making my one documentary film.

To sum up, dealing in any form of art demands hard work and business acumen that takes into account aesthetics and audience appetites. The disparity in performance of products (that ugly word) must be offset through volume and/or other means. (In New Day, we used a ‘share ladder,’ which was a math formula that provided relief to the lowest-selling titles and their makers by taxing, to a tolerable extent, the top-sellers.)

In my next post in this subseries, I’ll discuss what I’ve learned about the current state of the book-publishing industry through my research thus far.

Thanks for reading, and please remember to click the ‘like’ button!

A good read. Can't wait for the next part.